In the town of the two young lovers, Verona, I am suddenly reminded of the degree of partiality of my perception as I stand before a Madonna with the Child painted on panel by Alvise Vivarini some five hundred years ago. The picture has been cleaned and worn and gradually reduced to a ruin, but retains enough of its original radiance to catch a passing visitor to the Museo di Castelvecchio. The chubby figure of the Child brings a surprising impression of volume, of firm and round form filling a place in the shallow space. The body is built up with thin, transparent layers of paint. Daylight covers the naked skin of the Child, is reflected by the bulging surfaces of the tiny body and by the cheek of the Madonna. But what delights me, so much that I ask Mats to come and look, is the technical virtuosity shown by Vivarini, a Venetian master working in the shadow of Giovanni Bellini, in making the Child’s body shine as from within. Somehow Vivarini has painted a body which is both solid and transparent, convincingly that of a baby, but representing a radically other kind of luminous purity than that of any newly washed baby child.

Mats says: “Have you noticed the background?” Only then I perceive the wall behind the Madonna, painted in aubergine purple, and the verdigris green cloth behind her head, with plaits marking the shape of a cross. The square cloth is a common detail, shared with Bellini, marking an atmosphere of intimacy combined with spatial, solemn abstraction. Did Vivarini ever imagine withdrawing the holy figures from their fictive space? The parapet of painted stone would remain, as well as the representation of two vertical areas of cracked purple and copper green. Today, the empty room is a privileged metaphor for the mystery of faith and emotions. It is accessible to us as long as we do not actively look for it. So easy to pass by, to focus on all kinds of obstructing forms and objects, and in this way fail to perceive the more or less visible background rea- lity that keeps surrounding us.

When Barnett Newman was a young man in New York of the 1920s, he developed a deep knowledge of the city’s architectural structures of brick and iron, glass and steel. This kind of structures are equally important to Mats Bergquist. A watercolour painting in red, yellow and blue, saved from his early years in Moscow, is a study of Russian imperial roofs. “We did not have much else to do than to look at churches, buildings and things”. Mats says, referring to the number of foreign countries in the capitals of which he spent his childhood and youth, being the son of a diplomat. The local architecture may have represented some kind of constancy to him, in contrast to the temporariness that was a precondition for his residence. Be as it may, it remains a fact that Bergquist has a predilection for using significant structures found in architectural solutions in his creative work.

He transfers the interplay of broken horisontals and verticals in a Chinese trellis-win- dow into a pictural composition, giving it reminescent of Mondrian. In his collages Bergquist transforms into symbolic statements the short and flat cramp-irons that join the slabs of the low border walls along the canals in Venice. They seem to signify something close to the irons obliquely attached all over the Venetian lime-washed brick fronts, like wound stitches, a structure that he used in the form of thin diagonals in a series of copper paintings some years ago.

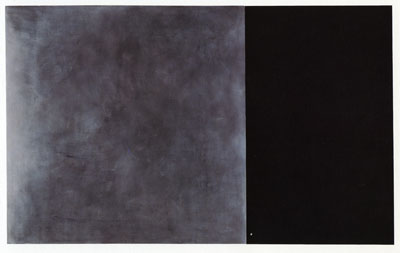

The vertical line which separates the window border from the adjacent wall, and the relationship of both to the slow slant of the roof, are details that fascinate him at the present, and so does the quiet insertion of the low step of the entrance door into the wall surface, set in one of the corners of the courtyard of a villa designed by Palladio. The seasons perform a continuous intercourse with the North Italian region where Bergquist lives at present; this spectacle, and the ever changing moods of the daylight enter into his painting in the form of vertical, monochrome rectangles which are coupled, and varied, and repeated within a keyboard of subdued colour shades. The green and purple vertical fields of Alvise Vivarini are of an almost identically to those of Mats Bergquist, whose Suite of Landscapes is linked to the innovative and tradition-establishing work of Barnett Newman, not least the late graphic series.

In his preface to 18 CANTOS, 1964, Newman writes: “I am not print-maker. Nor did I intend to make a ‘set’ by introducing superficial variety. These cantos arouse from a compelling necessity – the result of grappling with the instrument. To me that is what lithography is. It is an instrument, – for me , it is an instrument that one plays. It is like a piano or an orchestra, and as with an instrument, it interprets. And as in all the interpretive arts, so in lithography, creation is joined with the ‘playing’; in this case not of bow and spring, but of stone and press. The definition of a lithograph is that it is writing on stone.

- I have been captivated by the things that happen in playing this litho instrument: the choices that develop when changing a color or the papersize.

- Here the cantos, eighteen of them, each one different in form, mood, color, beat, scale and key. There are no cadenzas. Each is separate. Each can stand by itself. But its fullest meaning, it seems to me, is when it is seen together with the others”. This is also the case with Bergquist’s musical Suite of Landscapes.

When Mats Bergquist forms his large panels into bulging surfaces – stretched with rough linen cloth, drenched with hare glue, covered with layers of chalk, and only then painstakingly covered by coating and abrasion of its layers of mineral pigments and wax, which are finally turned into a state of intensely shining opaqueness – he keeps to a one thousand years old tradition established to represent and interpret the reality of the holy. The chiaroscuro of his large paintings may recall the smoky haze of mantles and skies characteristic of Tintoretto, but more than that they wish to mediate something of the elevated immanence with which Vivarini and his 15th century collegues filled the picture of the Madonna and the Child.

The geometric form that Barnett Newman talked about as “a living thing” and as “a magically active mediator” – as opposed to “a formal abstraction of a visual fact” – that form is also that of Mats Bergquist. His Icons invite the human face to meet “the other” face in a place which in the late 20th century is constantly given the form of a screen, a divine mask.

Det är i de unga älskandes stad, Verona, som jag påminns om hur partiell min varseblivning är. Det sker inför en Madonna med Barnet, målad på pannå av Alvise Vivarini för femhundra år sedan, med åren tvättad och försliten till en bildruin, men med tillräcklig utstrålning i behåll för att fortfarande hejda en förbipasserande besökare på Museo di Castelvecchio.

Barnets knubbiga gestalt förmedlar ett överraskande intryck av volym, av fast och rund form som tar sin plats i rummet. Kroppen är uppbyggd av tunna lasyrer i skikt på skikt. Det infallande ljuset täcker in dess nakna hud, reflekteras av den lilla kroppens välvda ytor, liksom av Madonnans kind. Men det som gör ett så starkt intryck på mig att jag ber Mats komma och titta är Vivarinis, venetiansk mästare i Giovanni Bellinis skugga, virtuosa teknik som får Barnets kropp att lysa inifrån. Hur det nu har gått till har Vivarini åstadkommit en kropp som är på en gång solid och genomskinlig, tillhörig ett levande spädbarn men genomträngd – lysande – av en renhet av annat slag än det tillstånd som varje nybadad jordisk baby företer. Mats säger: ” Har du sett bakgrunden!” och nu ser jag väggen bakom Maria, mörkviolett som aubergine, och den ärggröna duken bakom hennes huvud, med skarpa vecklinjer som tecknar ett kors. Det är ett konventionellt arrangemang, övertaget från Bellini, och markerar intimitet i kombination med rumslig, upphöjd abstraktion. Gjorde Vivarini någonsin det enkla tankeexperimentet att avlägsna figurerna ur rummet? Om Madonnan och Barnet lyfts bort återstår, bortom förgrundens målade stenparapet, ett möte mellan två vertikala färgfält, utförda i svartsprucket lila och koppargrönt. Det tömda rummet är vår tids rum för trons och känslans mysterium. Det gör sig tillgängligt när vi just inte söker det. Så lätt att gå förbi, att fokusera på alla de former och föremål som står i vägen, och därmed undgå att varsebli den fond av mer eller mindre synlig verklighet som hela tiden omger oss. Liksom den unge Barnett Newman i 1920 talets New York av tegel och järn, glas och stål studerar Mats Bergquist sådana utsnitt ur verkligheten som de flesta går förbi. En målning i röda, gula och blå vattenfärger från barndomsåren i Moskva återger ryska lökkupoler: “vi hade inte så mycket annat att göra än att se på kyrkor, hus och saker” säger Mats och hänvisar till sin uppväxt som diplomatbarn i ett antal främmande länder. Kanske representerade den lokala arkitekturen ett slags beständighet jämfört med den tillfällighet som var ett villkor för hans egen vistelse? Hursomhelst finner han betydelsebärande strukturer i byggnadskonstens funktionella och estetiska lösningar, och använder dem med förkärlek i sitt bild- skapande.

Spelet av brutna, samverkande horisontaler och vertikaler i ett fönstergaller i Kina får, sti- liserat till bild, en rytm i Mondrians anda. Korta, platta järnkrampor som kopplar murblocken längs Venedigs kanaler omvandlas i collagets form till symboliska yttranden. Deras innebörd ligger nog nära de snedställda järnbanden, så lika sårstygn, som häftar över de venetianska fasaderna av brukputsat tegel, och som han för några år sedan renodlade till tunna diagonaler i några kopparmålningar. Lodlinjen som skiljer fönsteröppningen från intilliggande muryta, och bådas relation till takets långsamma fall, hör till de detaljfeno- men som upptar honom nu, liksom det låga trappstegets stillsamt unika infogning i murytan under ytterdörren i ett gårdshörn till en villa som Palladio ritat.

Men även årtidernas umgänge med det nord- italienska landskapet och dagsljusets jämnt växlande stämningar abstraheras in i hans måleri och ges formen av ark med vertikalt parställda, monokroma fält som dubbleras, varieras och upprepas inom en återhållen färgklaviatur. Alvise Vivarinis stående par av fält i grönt och violett är till förblandning lika Mats Bergquists motsvarande kombinationer, som i sin tur är länkade till Barnett Newmans absolut grundläggande verk, i synnerhet det senare grafiska.

I sitt Förord till 18 CANTOS, 1964, skriver Newman: “Jag är ingen grafiker. Inte heller avsåg jag att göra en ‘serie’ genom att presentera variationer på en yta. Dessa cantos uppstod av nödtvång – resultatet av min närkamp med instrumentet. För mig är detta vad litografi är – ett instrument att spela på. Det är som ett piano eller en orkester, och som fallet är med ett instrument, det återger. Och som i alla återgivande konstarter, så även i litografi, förenas det skapade med spelandet, i detta fall inte på stråke och sträng , utan på sten och tryckpress. Definitionen på litografi är att det är skrift på sten.

- Jag har ‘spelat’ i hopp om att frammana allt som ligger i instrumentets förmåga.

- Här är cantos, arton stycken, var och en olika i fråga om form, stämning, färg, rytm, skala och tonart. Här finns inga kadenser. Var och en är fristående.

Var och en kan stå ensam. Men sin fulla betydelse får den, tycker jag, då den ses tillsammans med de andra.” På samma sätt förhåller det sig med Mats Bergquists musikaliska Lands kap s s vit.

När Mats Bergquist skulpterar stora pannåer till bukiga ytor, spänner dem med linnelärft, bestryker dem med harlim, bygger upp och slätborstar kritgrunden i skikt efter skikt, och först därefter tålmodigt arbetar fram själva målningsytan genom att ömsevis lägga på och slipa av dess skikt av jordpigment och vax som poleras till dovt levande glans, då följer han arbetsmetoden i en snart tusenårig tradition skapad för att återge det heligas verklighet.

Även om ljusdunklet i hans stora målningar mest erinrar om rökiga sjok av mantlar och himlatöcken av Tintorettos hand syftar de samtidigt till att förmedla något av den upphöjda immanens som 1400-talsmästarna gav bilden av Madonnan och Barnet.

Den geometriska form Barnet! Newman talade om som “ett levande ting” och ” en magiskt verksam förmedlare” – till skillnad från “en formål abstraktion av ett visuellt faktum”- den formen är också Mats Bergquists.

Hans “ikoner” inbjuder det mänskligas sida att möta “det andra” på en plats som i vår sena tid ständigt definieras som formen av en skärm, en gudamask.